NASA rockets create artificial clouds beneath the glowing auroras in Norway (photo).

NASA rockets seed artificial clouds below glowing auroras in Norway (photo) (Image Credit: Space.com)

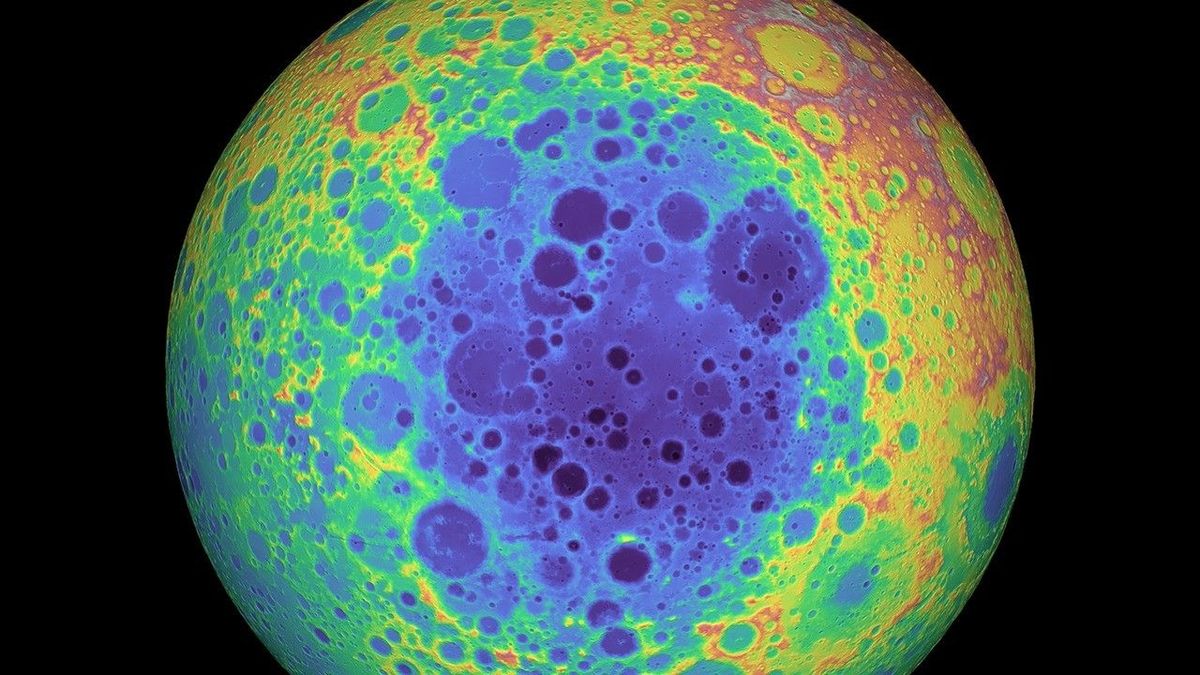

It’s not every day you get to watch a rocket launch into a sky glowing with colorful auroras — and it’s even rarer to see that rocket leave swirling clouds in its wake as part of a NASA science experiment.

But that’s exactly what Ivar Sandland of Bodo, Norway saw on Nov. 10 during a minor geomagnetic storm. Sandland operates Nordland Adventures, a tour and adventure company in Northern Norway.

“I went on a road trip from Bodo to Tromso to visit my daughter, camera always at the ready,” Sandland told Space.com. “On the way back (halfway), I stopped by the foot Mt. Stetind – Norway’s national mountain. I’ve always wanted to see Northern lights above the summit. It happened.”

“When I saw the rocket launch, I was very surprised,” Sandland said. “I assumed it was a very strange kind of cloud. Then checked from where it came from and figured out it could be from Andøya Space Center. The next day I read on local news there had been a rocket launch.”

As it turns out, that rocket launch was actually a double-header, and both rockets launched were part of NASA’s Vorticity Experiment (VortEx). The project seeks to better understand how energy flows through the turbopause, a portion of Earth’s atmosphere where the mesosphere and the thermosphere meet some 56 miles (90 kilometers) up.

To study these interactions, researchers launched a sounding rocket (a smaller, sub-orbital vehicle used in scientific research) loaded with trimethyl aluminum, a compound used in electronics and semiconductor fabrication.

Once released into the air, the wisps of trimethyl aluminum formed swirls and vortices in the sky that can help reveal how gravity waves behave and interact at this level of the atmosphere.

![NASA VortEx Campaign from @Andøya Space [LAUNCHED] | Day 14 - YouTube](https://satellitenewsnetwork.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/nasa-rockets-seed-artificial-clouds-below-glowing-auroras-in-norway-photo_6736a8ce373b9.jpeg)

Andøya Space Center is a rocket launch facility on Andøya island in northern Norway that hosts frequent launches of sounding rockets. Due to its location near the Arctic Circle, the site is ideal for launch experiments aimed at studying geomagnetic activity, auroras and the effects of space weather.

That’s because when charged particles from the sun reach Earth, our planet’s magnetic field funnels them toward the north and south poles. When these particles interact with atmospheric gases, they release energy in the form of light, creating the stunning light shows we call the aurora borealis, or the northern lights, and the aurora australis, or the southern lights.