“It’s akin to capturing a photo of lightning”: How astronomers swiftly pursued the tiniest asteroid ever observed.

‘It’s like taking a picture of lightning’: How astronomers raced to track the smallest asteroid ever seen (Image Credit: Space.com)

Astronomer Teddy Kareta had spent countless nights over the years observing various objects across our solar system using Arizona’s Lowell Discovery Telescope, or LDT. On Nov. 19, 2022, he set his alarm to ring shortly before midnight, in preparation for what he presumed would be a quiet observing night — and woke up to missed calls and messages from his boss. Those pings, he recalled, “more or less could be summarized as, ‘Dude, you gotta get on the telescope right now! What are you doing? Pick up!’”

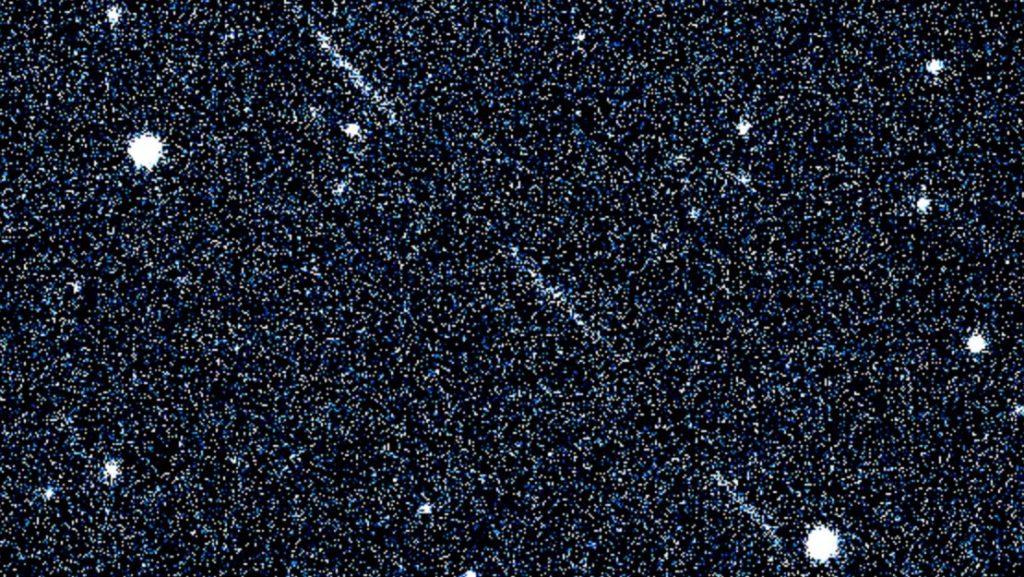

Just two hours before those calls, at 11:53 p.m. EST (04:53 GMT), asteroid-spotting telescopes in Arizona’s Catalina Mountains had reported the discovery of a tiny but bright asteroid on a trajectory that took it northward over Arizona’s clear, dark skies before leading it to a crash somewhere around Lake Erie and Lake Ontario, near the U.S.-Canada border.

The space rock, named 2022 WJ1, was most likely a run-of-the-mill chondrite, the most common type of meteorite, specimens of which land on Earth undetected nearly every day. Yet the fact that it was only the sixth asteroid ever discovered before it grazed Earth’s atmosphere and turned into a fireball had Kareta and his team racing to observe it before it disappeared into our planet’s shadow.

“Without question, it was the most exciting hour of my job that I’ve ever had,” Kareta told Space.com in a recent interview. “In some sense, we ended up getting a world-quality dataset on a fundamentally extremely common phenomenon.”

Related: Asteroid the size of 3 million elephants zooms past Earth

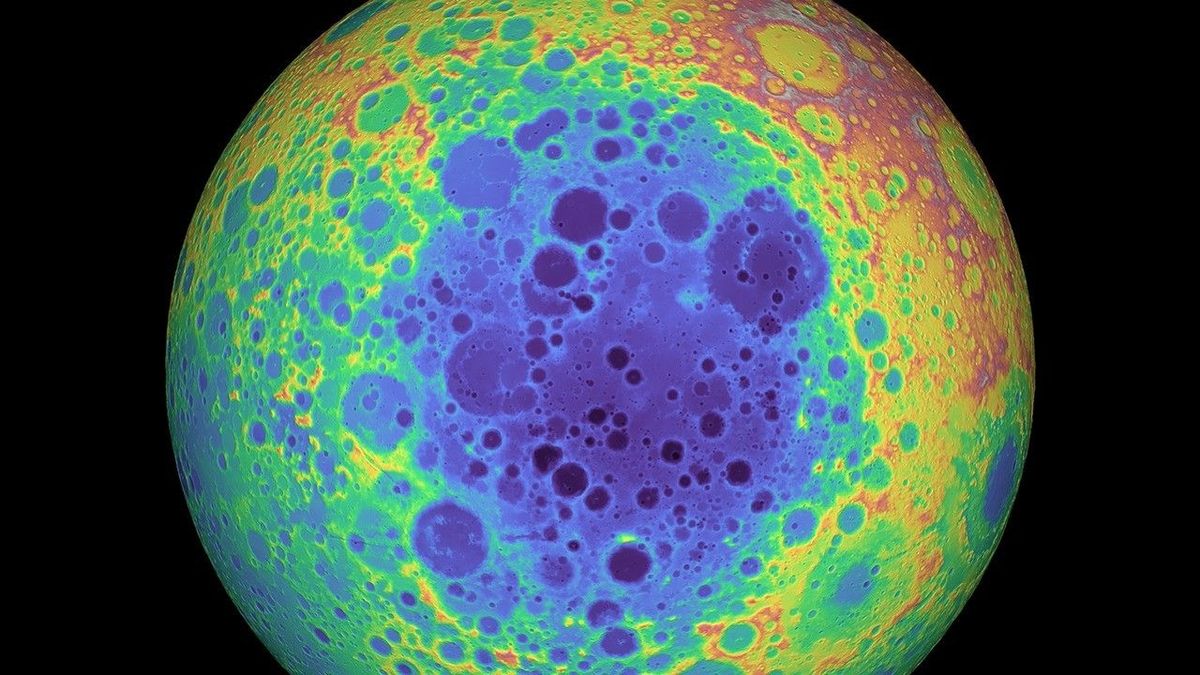

LDT imagery showed 2022 WJ1 to be just 16 to 27 inches (41 to 69 centimeters) wide, making it the smallest asteroid on record to be properly measured in space. Because the diminutive rock kept getting closer to Earth, and moving faster, with each frame, the telescope had to slew at an astonishing 5 degrees per second to maintain stable images — a pace that even larger telescopes would struggle to match. “It was loud enough that I saw the telescope operator, Ben, jump in his chair,” said Kareta.

Soon, the rock flew out of LDT’s view and into that of seven observatories around the world, a number of skywatchers in both the U.S. and Canada, and a network of meteor cameras operated by the University of Western Ontario. Those cameras managed to capture the stunning, softball-sized fireball glowing a vibrant green as it streaked across the sky before disappearing from view.

“It’s like taking a picture of lightning,” Kareta said. “the best you usually can do is, you take a bunch of pictures and hope one of them has the flash in it.”

Researchers suspect the vast majority of the 330-pound (150 kilograms) asteroid vaporized prior to its crash, and winds wafted almost all fragments into Lake Ontario. A large, 30-pound (13.6 kg) chunk may have landed on the edge of the lake, but recovery efforts the morning after that focused on the shoreline, an adjacent farmland, as well as site visits to nearby homes and businesses turned up nothing. A subsequent blizzard that dumped a couple of feet of snow in the area complicated the search, and further efforts in spring 2023 amounting to several hundred person-hours resulted in no finds.

“We may have lost the easiest time to look for it,” said Kareta, a postdoctoral researcher at Lowell Observatory.

Someone may still stumble upon pieces of the asteroid, but two years of exposure to the elements may have morphed it into a relatively unremarkable form compared to its distinctly scorched profile when it landed, Kareta said. “If you just found this rock in your yard, I’m not sure you’d necessarily bat an eye on it.”

The researchers consider it tremendously fortunate that 2022 WJ1 happened to fly over Arizona’s skies at night before burning up in the view of the University of Western Ontario’s watchful cameras. This rare event allowed astronomers to study the same object using different techniques for the first time.

Telescope observations measured remarkably well how the object reflects light, revealing 2022 WJ1’s external characteristics such as its silicate-rich surface, a relatively unsurprising feature common to most meteorites found on Earth. Meanwhile, images from meteor cameras captured the rock breaking apart in its final moments, giving astronomers insight into how strong and cohesive the rock might have been.

“Everyone wants to get a bunch of firsts on their resume, but I don’t think any of us were thinking about that at the time,” said Kareta. “It was closer to, ‘You mean we can point the telescope at the rock that’s gonna hit Earth? Of course we ought to do that!’”

To Kareta, the fireball event was also reminiscent of the shooting stars that captivate children and adults alike. “This is the kind of event we looked at, the kind you tell your friends about,” he said. “The fact that this is such a mundane thing — one could have happened during our conversation — it almost feels wild to say this is the first time someone has done this.”

Related: What are asteroids?

Forthcoming advances in the coming decade, chiefly telescope technology and expansions of meteor camera networks, should make discovering more future fireballs well ahead of the current norm of just a few hours a common — but no less mundane — occurrence.

For instance, one of the key objectives of the upcoming Vera C. Rubin Observatory in Chile is to enhance planetary defense by detecting more such space rocks. Set to begin operations next year, the observatory will employ the world’s largest digital camera to capture images of the southern sky every night for at least a decade, with each image covering an area equivalent to 40 full moons. Scientists expect this cadence will enable the observatory to identify up to 2.4 million asteroids — nearly double the number now cataloged — within its first six months of operations.

“We are entering a new era,” said Kareta. “We did some really cool science here, but it’s probably not gonna be that long before our study looks boring compared to what people are pulling up in a couple years, and I think that’s cool.”

This discovery is described in a paper published Nov. 22 in the Planetary Science Journal.