Hubble Telescope observes the Milky Way taking gas from its neighboring galaxy.

Hubble Telescope witnesses Milky Way strip its galactic neighbor of gas (Image Credit: Space.com)

In its galactic neighborhood, the Milky Way can be something of a bully.

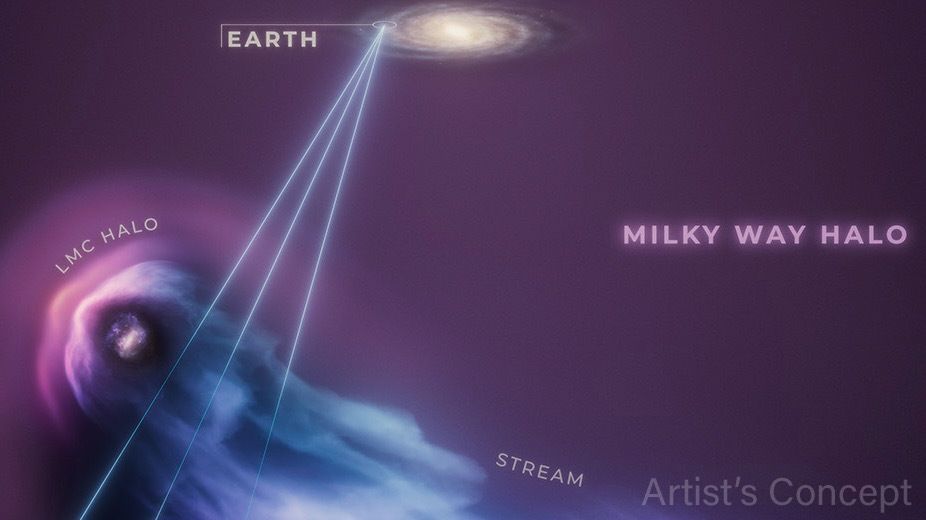

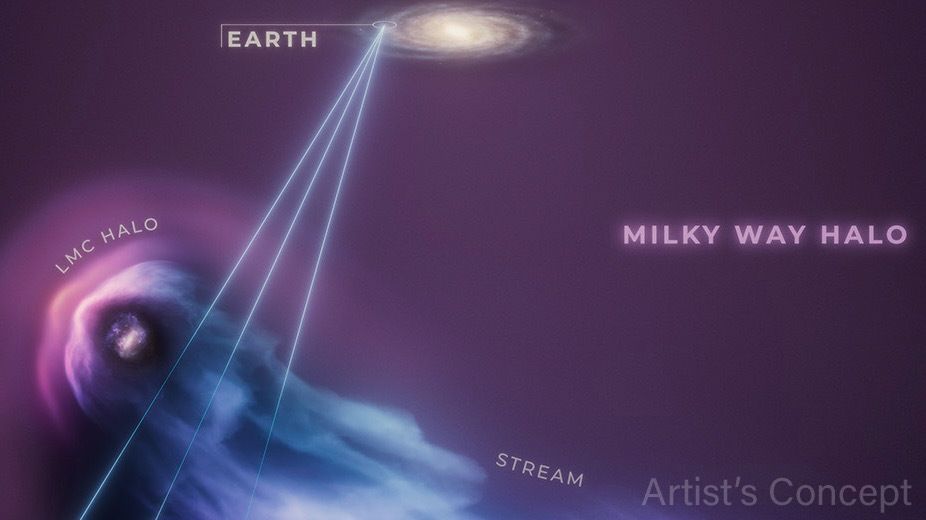

Our galaxy’s two closest neighbors are two dwarf galaxies known as the Large Magellanic Cloud (LMC), and the Small Magellanic Cloud (SMC). Being much smaller in mass (the LMC is 10% the mass of the Milky Way, for instance), these nearby galaxies are largely at the gravitational whim of ours.

When we look at a typical galaxy, we can see bright stars at its center. As your eyes move outward from the center, the concentration of stars tends to dissipate — ultimately disappearing completely. However, beyond the dense stellar neighborhoods of a galaxy is a halo of gas, dust and wandering stars that extend far beyond the realm’s visual borders.

The same goes for the LMC and the SMC.

A brand new study based on Hubble Space Telescope observations has thrown weight behind our galaxy’s reputation as a bully, showing that the size of the LMC’s halo is around ten times smaller than halos of other galaxies that have the LMC’s mass, which hints at a past incident with the Milky Way in which our galaxy stripped the LMC of some of its material. Researchers used observations of the LMC from Hubble’s ultraviolet vision.

“The LMC is a survivor,” Andrew Fox of AURA/STScI for the European Space Agency in Baltimore, who was principal investigator on the observations, said in a press release.

“Even though it’s lost a lot of its gas, it’s got enough left to keep forming new stars. So new star-forming regions can still be created. A smaller galaxy wouldn’t have lasted — there would be no gas left, just a collection of aging red stars.”

Despite losing large swathes of its gas, the LMC has been able to hold onto a compact bubble of its former material — material that is crucial for the galaxy to continue to support star formation.

“Because of the Milky Way’s own giant halo, the LMC’s gas is getting truncated, or quenched,” Sapna Mishra, the lead author on the paper explained in a statement.“But even with this catastrophic interaction with the Milky Way, the LMC is able to retain 10 percent of its halo because of its high mass.”

Hubble’s ultraviolet detection capabilities made it the ideal instrument for this study. Researchers observed the LMC’s halo by using background light from 28 bright quasars, the brightest parts of active galactic nuclei, as “lighthouses” of sorts. This allowed them to see the halo’s gas indirectly through the absorption of the quasars’ background light.

Researchers used data from Hubble’s Cosmic Origins Spectrograph (COS) to break the light into its component wavelengths to reveal clues about the temperature, speed and composition of the gas in the halo.

Seeing the aftermath of the LMC get close in proximity to the Milky Way can help researchers understand the galactic dynamics of the early universe, from a time during which galaxies were much closer together and were forced to interact all the time. It also reveals to researchers how many variables can be at play during galactic evolution.

Next, researchers are aiming to get a peek at the LMC’s halo from a different angle.

“In this new program, we are going to probe five sightlines in the region where the LMC’s halo and the Milky Way’s halo are colliding,” Scott Lucchini, co-author of the research said in a statement. “This is the location where the halos are compressed, like two balloons pushing against each other.”

The study is yet to be published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters; a preprint can be found here.